Rhythm can improve coordination between perfect strangers and place them on the same wavelength, say researchers from the MARCS Institute at Western Sydney University.

They have found evidence that synchrony between the brains of two individuals does not simply result from, but actually causes interpersonal coordination.

Professor Peter Keller, research leader of the MARCS Institute’s Music Cognition and Action program, said this finding was remarkable because it provided a new platform for developing neurological interventions that could improve communication in group activities.

“This could apply to performance in musical ensembles, dance troupes and even collective decision making in time critical contexts, such as those faced by sporting teams and military combat units,” he said.

“Our research participants’ displayed an enhanced ability to coordinate their movements when we delivered synchronised rhythms into their brains via electrical stimulation at the surface of the head.

“This means that brain-to-brain synchrony is not just a by-product that results from two individuals doing the same thing; it is actually a collective mental state that can enhance coordination between two or more people.”

Dr Giacomo Novembre, who led the research study, said previous electrophysiological work in humans and animals demonstrated that different rhythmic patterns (or frequencies) of neuronal activity are associated with different cognitive functions.

“The specific frequency used to deliver rhythm to participants in our study, which was 20 Hertz (also called beta band), has traditionally been associated with motor processes, and in some cases, with neural processes that link our perception with our capacity for action,” he said.

“Our findings show for the first time that this state of brain-to-brain synchrony was a sufficient condition for the enhancement of interpersonal coordination, and might possibly enhance other forms of interaction and communication.”

The study involved 60 randomly selected individuals who formed 30 pairs.

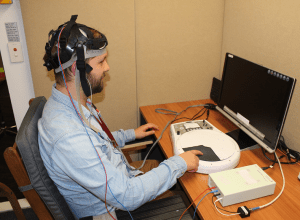

Each individual within a pair was seated in a separate room with no visual contact with the other person.

Paired individuals were required to perform a joint tapping task with their right index fingers while simultaneously receiving electrical current stimulation over their left primary motor cortices – the brain region that controls movements of the right hand.

Dr Novembre said because the finger taps triggered percussion sounds, participants could hear one another just as if they were playing a musical duet.

“What we found was that synchronisation across two brains increased the probability of two individuals, unknown to each other, tapping at the same time,” he said.

[social_quote duplicate=”no” align=”default”]“The human brain can be thought of as a very large orchestra. There are numerous populations of neurons that are activated together, each following a different rhythmic pattern.[/social_quote]

“When two neuronal populations follow a similar pattern, these are usually communicating with one another.

”While neuroscience typically focuses on rhythmic activity within an individual’s brain, our results highlight the importance of coordinated activity across separate individuals’ brains.

“Ultimately this leads to higher interpersonal synchronisation, which could benefit communication between people in many contexts.”

Click here for more information.